Justice & Reconciliation

Justice and reconciliation are critical components in the recovery of post-war societies, serving as one of the four pillars embraced by Knowledge4Peace. In the aftermath of violent conflicts, societies are often left divided and traumatized. Restoring trust, healing wounds, and holding accountable those responsible for atrocities are fundamental for long-term stability. Justice and reconciliation, as interconnected processes, play a pivotal role in transitioning from conflict to peace by addressing both the need for accountability and the restoration of social relations.

Justice in post-war settings often begins with transitional justice mechanisms, which include both legal justice and social justice frameworks. These mechanisms focus on prosecuting those responsible for serious human rights violations while also ensuring that victims receive recognition, reparations, and acknowledgment of their suffering. However, justice in post-war settings is not solely about punishing perpetrators; it also involves creating avenues for truth-telling and restoring dignity to victims. This is where the role of truth commissions and other transitional justice institutions becomes essential.

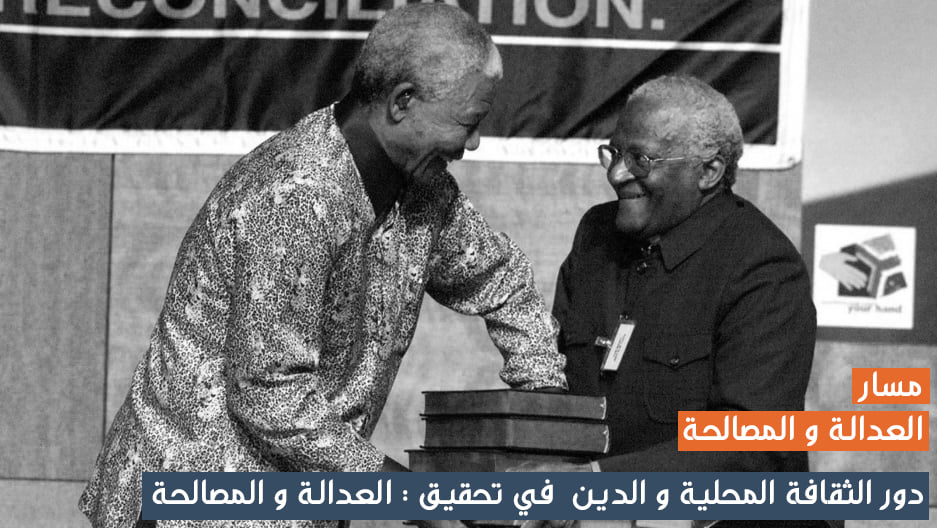

Truth commissions, such as the one in South Africa after apartheid, aim to uncover the facts about past atrocities and human rights violations. They provide a space for victims and perpetrators to share their experiences, allowing for a collective understanding of the violence that occurred. While the concept of “truth” is complex and often contested, truth-telling is vital for the healing process. It allows victims to have their pain acknowledged, and it creates an official record of events, which is important for historical memory and preventing future violence.

Confession, particularly from those who committed crimes during the conflict, plays a dual role in the justice process. On the one hand, it provides essential knowledge about the crimes committed, helping to fill in gaps in the historical record. On the other hand, confession serves as an acknowledgment of guilt, offering victims some degree of closure. However, as highlighted in various case studies, such as Rwanda’s Gacaca courts, confessions are not always fully genuine, and perpetrators may confess simply to reduce their sentences rather than out of genuine remorse. This complicates the reconciliation process, as victims may doubt the sincerity of these confessions.

Forgiveness, while often seen as a personal and voluntary act, is deeply intertwined with reconciliation efforts in post-war societies. Forgiveness does not mean forgetting the past or excusing the crimes, but it can serve as a pathway to restoring broken relationships between victims and perpetrators. Political forgiveness, or societal-level forgiveness, can also play a role in fostering reconciliation, as victims may choose to forgive in order to promote peace and move forward collectively. However, forgiveness must be approached carefully, ensuring that victims are not pressured to forgive without genuine remorse from the perpetrators.

Reconciliation is the ultimate goal of these processes, but it is a complex and multifaceted endeavor. Reconciliation is not just a single event or a declaration; it is a long-term process that involves rebuilding relationships and trust. In post-war settings, reconciliation often requires both individual and societal efforts. At the individual level, it may involve personal interactions between victims and perpetrators, where forgiveness and empathy can develop over time. At the societal level, it involves creating systems and institutions that promote social cohesion, prevent future conflicts, and ensure that all members of society feel included and protected by the state.

For reconciliation to be successful, it must be accompanied by a sense of justice. Without accountability for past crimes, reconciliation efforts may falter, as victims and survivors feel that their suffering has been ignored or minimized. Transitional justice mechanisms such as trials and truth commissions help balance the need for both justice and reconciliation by ensuring that those responsible for the most heinous crimes are held accountable while also creating opportunities for restorative justice and societal healing.

In countries such as Rwanda and South Africa, the processes of justice and reconciliation have been challenging but necessary for the rebuilding of their societies. In Rwanda, the Gacaca courts were established to address the massive number of perpetrators involved in the 1994 genocide. These courts allowed for community-based justice, where perpetrators could confess their crimes and seek forgiveness from their victims. While not perfect, the Gacaca courts helped to foster a sense of accountability and played a role in the country’s reconciliation efforts. In South Africa, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission similarly sought to balance justice with the need for societal healing by offering amnesty to those who fully confessed to their crimes under apartheid.

At Knowledge4Peace, justice and reconciliation are seen as integral components of building lasting peace. The organization emphasizes the importance of both holding perpetrators accountable and fostering a process of healing that allows societies to move beyond the violence of their past. This pillar encourages a comprehensive approach to justice that includes legal frameworks, truth-telling mechanisms, and reconciliation initiatives that bring together victims, perpetrators, and broader society.

In conclusion, justice and reconciliation in post-war settings are deeply interconnected and vital for sustainable peace. While justice provides accountability and recognition of the harm caused, reconciliation fosters healing and the rebuilding of relationships. Both processes are necessary for creating a stable and peaceful society, and they must be approached with care, ensuring that the needs of victims are prioritized and that the entire society is engaged in the process of moving forward.

دور الثقافة المحلية والدين في تحقيق العدالة والمصالحة بعد الحروب – The Role of Local Culture and Religion in Achieving Justice and Reconciliation After Wars

أهمية البحث عن الحقيقة وتحقيق التوازن المجتمعي The Importance of Seeking Truth and Achieving Social Balance

هل يمكن للحقيقة أن تكون محايدة؟ بين السياسة والعدالة في المجتمعات المتعافية من النزاعات – Can Truth Be Neutral? Between Politics and Justice in Post-Conflict Societies